Here is the text from my talk at the AAG conference last week. It was for a really great session organized by Joe Shaw and Mark Graham (who are at the Oxford Internet Institute) on “An Informational Right to the City”.

Everyday Code: The Right to Information and Our Struggle for Democracy

Introduction

Henri Lefebvre proposed a right to information, and he thought that right must be associated with a right to the city. I want to urge us to understand both those rights in the context of Lefebvre’s wider political project. That wider project was the struggle for self-management, what Lefebvre often called “autogestion,” and what I prefer to call democracy.

Lefebvre articulates his wider political vision in terms of what he called a “new contract of citizenship between State and citizen.”

This contract is made up of a series of rights, which include the right to the city, to services, to autogestion, and to information. Clearly this agenda looks very liberal-democratic; one might expect that a minimal State will guarantee individuals this list of rights. But this is not at all Lefebvre’s vision. Instead, he is calling for “a renewal of political life,” for a generalized political awakening among people. Lefebvre hopes this awakening will constitute a revolution, through which people decide to become active participants in managing their affairs themselves. This new tide of popular political activity, if it can sustain itself over time, will eventually make the State (and capitalism) superfluous, and they will wither away. And so Lefebvre is proposing a very strange sort of contract between citizens and State, a contract whose aim is to render both parties obsolete.

Key to understanding Lefebvre’s wider vision is this right to autogestion. In English it means “self-management,” and traditionally it referred to rank-and-file workers taking over the management of their factory from the factory’s owners and professional managers. Lefebvre advocated that kind of autogestion, but he also wanted to extend the idea, beyond workers as political subjects and beyond the factory as political arena, to a range of political subjects and political arenas. He was aiming at something people at the time called “generalized autogestion,” in which all people take up the project of collectively managing all matters of common concern.

That last idea is important, that autogestion is a project. It is not a utopia, not an ideal community at the end of history, without the State, in which people manage their affairs entirely for themselves. Autogestion is, instead, a project. It is a perpetual struggle by people to become increasingly active, to manage more and more spheres of their lives for themselves.

So of course information is critical here. Effective and enduring self-management, by whatever agents in whatever arenas, requires that people have access to and effectively use the information that is relevant to their common affairs. And so the right to information is a part of the contract that Lefebvre proposes. In our own liberal-democratic vernacular, the “right to information” would mean something like: individual citizens have the right to access information that is being kept from them for some reason, usually by the government. But if we understand the “right to information” in the context of Lefebvre’s wider project, I think we will conclude that access to information, people having information, is necessary, but it is not really the main point. What matters most, in the context of autogestion, is what people do with the information they have. Once they have access to it, do they engage with it? Do they appropriate the information—which is to say, do they make it their own—and put it into the service of the project of autogestion?

If we understand the right to information this way, with Lefebvre, I think we will tend to frame the problem of information differently than it is usually framed. The problem isn’t so much that we are being prevented from getting the information we need. There is more information available to us than we know what to do with. The problem is, more, how can we become active, appropriate the information available to us, and use that information effectively in our project to manage our affairs for ourselves.

And so I want to draw our attention away from much discussed struggles to gain access to information, like Edward Snowden and Wikileaks. While such struggles are germane to Lefebvre’s wider project, they tempt us to assume that once we have access, the struggle is won. But it isn’t. And so I want to draw our attention to the struggle to appropriate and use the information we already have access to. Are we engaging with it actively and incorporating it effectively into our political project of autogestion?

To do this, I am going to talk about something quite a bit less sexy than government secrets, or big data, or all the new forms of geographical information we use.

I am going to talk about the software that runs our personal computers. That is, I want to talk about how we use, understand, and interact with the information—the software code—that structures our everyday digital environments: window managers, system trays, power managers, and so on. These programs are, increasingly, the medium through which we engage with the world. Do we understand how they work? Are we able to? Do we care?

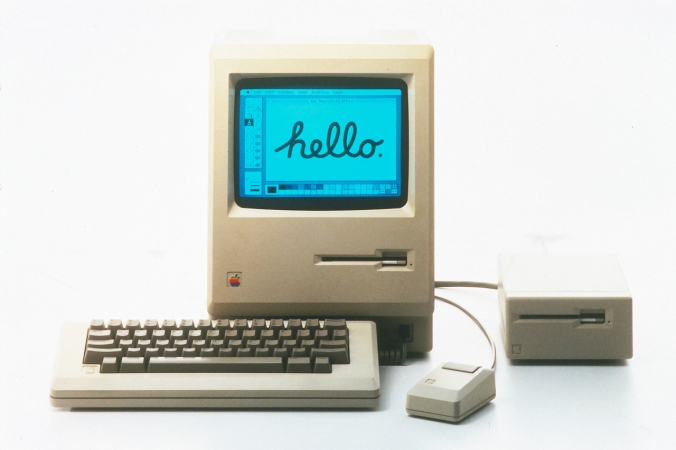

Everyday (Digital) Life: GUIs

The larger paper addresses three main topics, but it’s this first question of Graphical User Interfaces that I think sheds the most light on this issue of whether we use and appropriate the information on our desktops.

A graphical user interface (GUI) is a program that allows a user to issue commands to a computer without knowing the actual commands themselves. A GUI opens a window on the desktop and presents the user with buttons, drop-down lists, check boxes, and tabs with which the user can, through a series of mouse gestures and clicks, tell the GUI what changes s/he wants to make.

Let me take you through one very small example. On my machine, the monitor resolution is changed by issuing this command:

xrandr --output HDMI-0 --mode 1280x960

‘xrandr’ is the program that issues the command, the –output flag tells the computer which monitor to adjust, and the –mode flag tells the computer which resolution to set that monitor to. I can make these changes directly, by typing the command above into a terminal window and pressing enter. Or I can use a GUI. In my case that would mean using a mouse to click the “Launch!” button in the top-left corner of the desktop, which would show me a base menu of options. Clicking “settings” on that menu opens another menu, on which I would click “display.” Then the GUI opens a new window, and it makes a query to find out which monitors are available to use. It then presents me with an icon for each available monitor. I click on the icon for the monitor I want to change, then I select the resolution I want from a drop-down box that offers me all the resolutions that monitor is capable of. Then, behind the scenes, the GUI will issue the “xrandr” command above, and the resolution will change. At this point, most GUIs will even check in with the user and ask if the new resolution is acceptable, to which the user responds by clicking the “yes” button or the “no” button.

Nearly all of us use a GUI to change our monitor resolution. We rely on it. We don’t know how to change the resolution directly. We don’t know what command to issue. We don’t know how the command works; we can’t avail ourselves of the many powers it has. We don’t know how to find out the actual names of the monitors, the ones the computer uses, or what resolutions they can operate at. We need the GUI to help us. And it does. It doesn’t trouble us with the specifics: it issues the command in the background, out of our view. We are probably not even aware a command is being issued at all. The monitor just changes. The GUI takes care of it. It takes care of us.

While this example may seem almost painfully trivial, still, it matters to us whether the monitor is set to the right resolution. If it wasn’t, it would be hard to get work done. But even though it matters to us, we don’t really know how to tell the computer directly to behave the way we need it to behave. We are illiterate, most of us, unable to read and write the simple commands the computer understands and responds to. We need the GUI to read and write for us. We are helpless without it.

And so we users are alienated from the information that runs our desktops. In the paper I call this a “soft alienation,” rather than a hard one.

In hard alienation, we are being actively prevented from accessing information by some intentional means, such as a government’s claim to secrecy or a corporation’s claim to intellectual property. Soft alienation is alienation that we can overcome, often with only a little effort. To return to my xrandr example, no real barriers exist to prevent me from learning xrandr. It is installed by default on my operating system. Its manual is included, it’s only 2,100 words, and it’s comprehensive. Xrandr can be mostly learned in about a half an hour. It is a powerful command that is capable of much more than what the GUI can do. And yet most of us don’t learn xrandr. We rely on the GUI.

So in soft alienation, we are choosing to be alienated, choosing to let others produce and manage information for us. The impetus for this kind of alienation does not lie outside us, it lies inside us. The struggle against this alienation will be different from the struggles where ‘we’ confront ‘them’ because they are oppressing us. The struggle will be, instead, a struggle within, a struggle between the part of us that wants to be passive and alienated, and the part of us that wants to be active and master the information that matters to us.

How do we engage a struggle like that? I don’t think we should try to defeat our bad desires, those that want us to be passive and dependent. I think we should focus on our good desires—our desires to actively manage the information that runs our desktops—and we should try to cultivate those desires. What we need is simply to start doing the right thing, start building up our ability to access and master information. We need to read the xrandr manual, start issuing commands, and see what happens. When it works, we can try out other features of the command. When it fails, when we break something (which we will), we can figure out how to fix it, or we can turn to others who have had the same problem, and they can help us. As we build our strength in this way, by practicing, by exercising our good desires, I think we will develop a taste for it. We will come to enjoy the feeling of learning a command, issuing it directly to the computer, and seeing the changes happen. We will come to prefer that way of interacting with our machines over the alienation of the GUI. This feeling—call it pleasure, or joy, or delight—is vital. It will have to be there if we are going to succeed. It isn’t a cheap pleasure, the kind of thrill we get when we see the redesigned Apple OS for the first time.

It’s a deeper pleasure, slower burning but longer lasting, that we can settle into, that we can make a habit out of.

Conclusion

I have been focusing my attention on the desktop, on this little world we inhabit so intimately, and I have tried to give some account of what Lefebvre’s right to information would entail in that world. But of course this session is on “An informational right to the city.” And so what about the city, and the urban, both of which were so important to Lefebvre? In making the argument that our little desktop worlds matter, I am not saying, at all, that the city no longer matters. Both matter. However, I am willing to say that the two struggles are analogous, almost to the point of being isomorphic. In managing the information on our desktops for ourselves, we users must become active, aware, and alive; we must decide to take up the project of producing and managing this newly-vital realm for ourselves. The gist of the right to the city, as Lefebvre understood it, is the same: those who inhabit the city must take up the project of actively producing and managing urban space for themselves. They must overcome their desire to be ruled, to have urban space managed for them, and they must discover the delight of governing the city for themselves.

And of course the struggle for our desktops and the struggle for the city are only two of the many struggles that matter. When Lefebvre turned his attention toward the city and the urban inhabitant he was trying to generalize the concept of autogestion, beyond the factory and beyond the working class, to the city and the urban inhabitant.

There is no reason to think we should stop there. The school, the family, the military, the desktop: all are arenas in which we can pursue the project of autogestion. I am happy to think of these all as essentially equivalent political struggles. We shouldn’t nest or hierarchize them: a struggle for autogestion on the desktop is no more or less important than a struggle for autogestion in the city, or the home, or the school. Each moves us farther down a path toward autogestion, toward managing our own affairs for ourselves. Each teaches us the habits, skills, and attitudes we’ll need to maintain the struggle. Each trains us to know what it’s like to appropriate a sphere of experience, to take up the challenge of being the author of our own lives. Each reveals to us our own power to create, to manage, and to decide. Each helps us know what it feels like: the pleasure, or joy, or delight, of autogestion. Each is a little project—both individual and collective—to save our lives. What we need to do is not to rank them or prioritize them; we need to notice them, amass them, connect them together into a spreading project for generalized autogestion, into a spreading project for democracy.